More than 200 rare antibiotic-resistant genes were found in “nightmare” bacteria tested in 2017, according to a Vital Signs report released Tuesday by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“I was surprised by the numbers we found,” said Dr. Anne Schuchat, principal deputy director of the CDC.

The report focused on the new and highly resistant germs that have yet to spread widely. Still, a variety of resistant germs can be found in every state.

“Two million Americans get infections from antibiotic resistance, and 23,000 die from those infections each year,” Schuchat said.

Testing 5,776 isolates of antibiotic-resistant germs from hospitals and nursing homes, the CDC found that about one in four had a gene that helped spread its resistance, while 221 contained an “especially rare resistance gene,” she said.

“This wasn’t just a problem in one or two states,” Schuchat said, adding that the 221 rare genes were found in isolates gathered in 27 states from infection samples that included pneumonia, bloodstream infections and urinary tract infections.

Because this was the first year of testing for rare genes, the CDC does not have trend data, she said, but she hopes this won’t be the “beginning of an inevitable march upwards.”

The new report highlights the work of the CDC’s Antibiotic Resistance Laboratory Network, formed in 2016 to help detect antibiotic resistance in health care, food and the community.

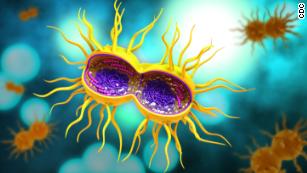

In 1988, health officials in the United States learned that some germs within one family of bacteria, Enterobacteriaceae, could produce an enzyme capable of breaking down common antibiotics. By 2001, the germs had begun to evolve, becoming more resistant to carbapenems and other antibiotic drugs. These carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, or CRE — dubbed “nightmare bacteria” by the CDC — spread rapidly in the US and around the globe.

Today, the CDC promotes an aggressive “containment strategy” that includes rapid detection tests and screening for reducing the spread of antibiotic resistance.

“CDC estimates show that even if only 20% effective, the containment strategy can reduce the number of nightmare bacteria cases by 76% over three years in one area,” Schuchat said.

While public health officials concentrate on containment protocols, each of us can help limit antibiotic resistance by keeping our hands clean and disinfecting cuts, the CDC recommends. Also, it is important to talk to health care providers about preventing infections through vaccines and other measures while informing them whether you have been treated in another facility or country.

“Even in remote areas, the threat of (resistant) pathogens is real,” Butler said. Because patients transfer from hospitals and nursing homes, germs can spread across the nation.

Dr. Arjun Srinivasan of the CDC’s Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion emphasized the hopeful message contained in the new report.

While a single provider may be at the center of each case of antibiotic resistance, “no provider has to go it alone,” he said. Working with hospital and state infection control teams, the spread of a rare infection can be stopped.

It’s not a “one and done” deal, Srinivasan said. Health officials “keep at it,” he said, until the spread of a potentially deadly infection is controlled.